User Tools

Sidebar

This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Big Data

In short

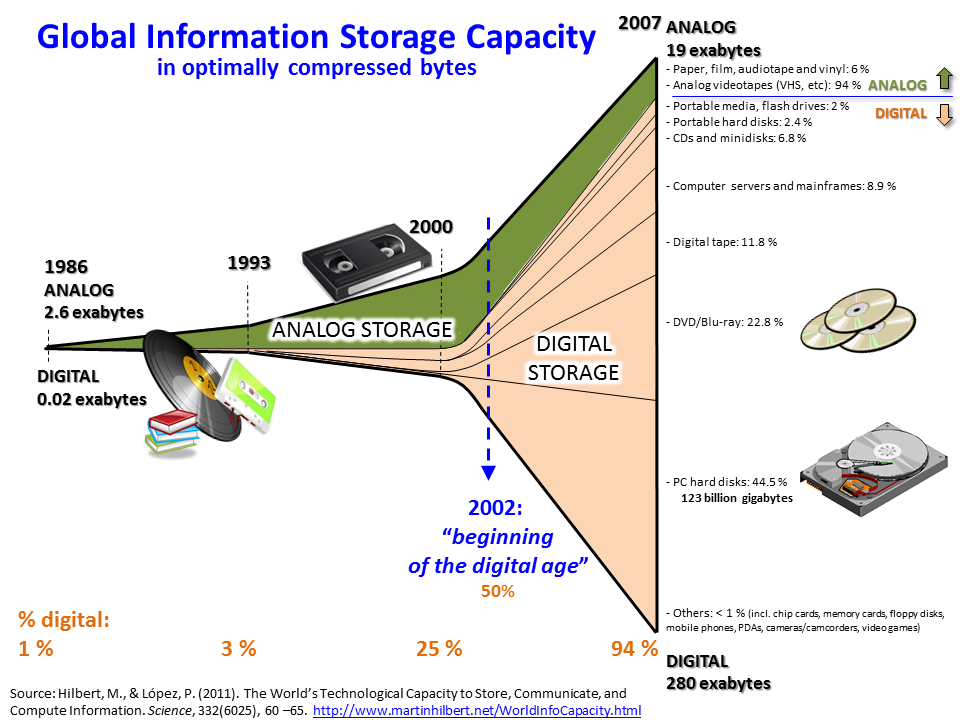

Big data refers to large amounts of data that are collected, stored, processed and analysed using specific procedures. It is impossible to imagine economy and society without data; they are obtained from people's activities on the Internet and via mobile phones, are the basis for activities on the financial markets, are relevant in the energy industry, health care and transport; they are covered by the use of credit and customer cards, surveillance cameras, airplanes and vehicles, chatting via WhatsApp, postings on Facebook (or other providers), the use of assistive devices such as Alexa, Curtana or Siri, the use of fitness wristwatches and soon the use of “intelligent refrigerators”, the smart table lamp, face recognition at train stations, body scanning at airports, “social scoring”, and so on. It is estimated that the amount of data having been collected doubles every two years.

Data in large quantities, “big data”, are the “oil” of the digital age. They represent a significant economic factor and growth engine. Firstly, because they serve to optimise production processes. On the other hand, because new products – such as the “intelligent” watch – are created on the basis of technologies that generate data.

The development and use of data on a large scale raises questions about the political control: Who has access to the data? How can the misuse of data be prevented, how can transparency be ensured? How can it be prevented that data are removed from social, democratic control, for example by handing it over to secret services? Attempts to regulate the development and use of data to protect personal rights are formulated in data protection regulations.

Facets of a Term

Big data refers to large amounts of data that are collected, stored, processed and analysed using specific procedures. This is associated with great hopes. At the same time challenges and risks are discussed. Above all, big data is political. Why? Read it yourself!

First of all, a brief introduction to some aspects - as one of many presentations published on the Internet:

Questions about the film:

What are big data according to this representation?

What can you learn about data storage?

Which aspects you know about big data were not mentioned?

Why Big and not Small?

Big data exceeds the usual possibilities of data transfer and data storage. It does not work like this to send a 150 MB attachment in an e-mail. This is “too big”. It is the same when several aircraft simultaneously exchange data with the air traffic control of an airport, which monitors the flight. The amount of data is too large to be stored on conventional media.

Big data, however, does not only mean large amounts of data. The term refers to several dimensions:

- volume – volume, data volume,

- velocity – speed with which the data volumes are generated and transferred

- variety – range of data types and sources,

- veracity – authenticity of data.

These technological dimensions are extended by the aspects of

- value – the added value for companies (hoped-for profit growth) and

- validity – ensuring data quality.

While big data is characterised by the fact that they are not stored and processed for instance with a simple PC, how is it done? In the video, this is explained using Apache Hadoop as an example, a framework (“programming framework”) by which data are processed in parallel, where they are divided and stored on different computers and thus backed up.

Big data is more than that. It also means an active handling and use of these data. The stored information are analysed (data analytics). It is expected, that this will provide insights for the improvement of products, the development of new products, the most accurate possible advertising of goods and services, for science and research, justice and administration, but also for the military and secret services. There is no lack of “raw materials” for data analysis: it is estimated that the volume of data has doubled every two years since 2011. What may seem abstract may become more 'comprehensible' if one imagines the activities that have led to the acquisition of data: research on the Internet, via search engines such as Ecosia, Startpage or Google, posting on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or similar, when chatting (WhatsApp, Telegram, Signal, Threema etc.), cashless payment by credit card, booking a train, bus or flight, body scanning at airports, visiting the doctor, online shopping, using a fitness watch, using assistants such as Alexa, Cortana or Siri, using navigation systems such as GPS and much more. Data is collected by companies, in many different ways by authorities, by surveillance cameras in public places, in train stations or private facilities, by face recognition, networked technology in houses (smart homes), the “intelligent” car, when making phone calls, writing e-mails and much more. So-called metadata are often obtained, i.e. data that describe an object and are combined (indexed) into categories. One can imagine this similar to a catalogue in a library.

In addition to those already mentioned, the analysis of large amounts of data obtained is used in many other fields: Crime prevention, analysis of web statistics, investigation of weather data, risk assessment and classification of insurance contributions (health, car and other insurance companies), in medicine, fraud detection, precision agriculture, investigations into the development of earthquakes and epidemics, population migration, traffic congestion, marketing and influencing purchasing behaviour, the evaluation of movement profiles and much more. Data analyses have also been used in politics and the steering of political opinions. The company Cambridge Analytica has become well-known. It had the reputation of having created several million personality profiles of Facebook users, which offered information for targeted election advertising (in the US presidential election campaign in 2016, in the referendum on Brexit 2016). However, the accuracy of the analyses was highly doubtful.1)

Big Data – Big Market

Data are considered the fuel of the 21st century – as the central raw material for economic growth. Companies are focusing on using big-data technologies such as in-memory data management, analytics, artificial intelligence and machine learning to optimise business processes, gain competitive advantages over others, create new business models and new markets, for example with a view to combating climate change: “Climate needs data and lots of it.”2) As it ist not easy to imagine the data volume, not only big, but also vast data or data lakes are spoken of.3)

Challenges from a company's point of view are described as “data chaos”, the pressure for speed and time advantages and the error-proneness of data analyses.

From the perspective of employees and consumers, the spying and, based on this, the diagnosis of employees, often referred to as “people analytics”, is a trigger for criticism. The aim is to bring together the data traces left behind by employees. Among other things, algorithms are used to determine the mood in the company, to gain information about who has influence or is unlikely to have influence, or to predict future behaviour, e.g. whether someone is inclined to resign. People Analytics is becoming more and more widespread, not only in individual divisions of the company. In Germany this practice is subject to co-determination, as personal data are used. However, those who are already on the move with fitness bracelets, smart watches and the like practice a kind of people analytics themselves – and may not be sure whether the data are only accessible to themselves.

Bracelets are also used by the online company Amazon, using radio and ultrasound technology. They are used to record the hand movements of employees precisely. For example, the bracelet vibrates when a warehouse worker misplaces a package. It can also be used to check whether an employee is working, taking a break or visiting the rest room.

Big Data – Big Brother

The storage and collection of data is also politically explosive. In Germany, a law on so-called data preservation was introduced in 2007, later rejected by the highest court and is currently suspended as it is under review by the European Court of Justice. It stipulated that data of contractual partners must be “stored” without cause and for certain periods of time. These include, in the case of telephone calls, the telephone numbers and location data of the call partners, and in the case of Internet use, the time and IP address used. In this way, the communication behaviour of citizens and their social relationships should be determined. The data would have made it possible to create personality profiles. The contents of the communication should not be accessed, only for SMS and MMS.

A distinction must be made between data preservation and the monitoring of telecommunications by government agencies and secret services. This data collection includes content and in this case is only permitted for the future from the beginning of the surveillance. With data preservation, on the other hand, the providers (i.e. ICT companies) are obliged to make stored information available to the authorities or state's security bodies.

Data preservation is opposed by the secrecy of telecommunications and the right to informational self-determination. The law and practice are therefore controversial. It has been the subject of legal proceedings on several occasions. On 21st December 2016, the European Court of Justice confirmed that data preservation without cause is illegal. On 25th September 2019, the highest German court, the Federal Constitutional Court, decided to refer the final interpretation of the Data Protection Directive for Electronic Communications (Directive 2002/58/EC) to the European Court of Justice. Until then, data preservation in Germany is suspended.

In France, however, data preservation was introduced in 2006. Data can be retained for one year without any reason.

In Romania, data preservation of six months had been introduced by law. However, the Romanian Constitutional Court has abolished it. The reason given was that data preservation without suspicion invalidates the presumption of innocence, declares the entire population to be potential criminals and violates Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The reason given for data preservation is that it enables crimes to be prevented or better prosecuted. The benefit is nevertheless considered to be minimal: Attacks could not be prevented. Critics also see this not only as a violation of the right to informational self-determination, but also as the danger of extending behavioral records to all areas of life, in principle every piece of information could be relevant once for the prevention or prosecution of crimes.

But it is not just the spying of data by companies and government agencies. Another challenge for the right of personality is the fact that those affected are not sufficiently informed, give their consent to the use of data without much guile or are not aware of the processing of their personality and movement profiles, which may be viewed critically. The aforementioned susceptibility to error must also be taken into account: “Linking information that are in themselves unproblematic can lead to problematic findings, so that you suddenly belong to the circle of suspects, and statistics can make you appear to be unworthy of credit and risky because you live in the wrong part of town, use certain means of transport and read certain books.”4)

Protection against “big brother” is therefore seen in the anonymisation of data, for example through proxy servers or the Tor network. But even these strategies are doubted, because even such data can be decoded again. One way out would be effective data protection as well as the highest possible transparency and broad social, democratic control of data flows.

Big Data – Big Democracy

In the discussions about big data / vast data, a strong assumption is implicitly made: The citizens live in a democratic system. But what would happen to data, fundamental rights and freedoms if a society were not democratically constituted? Would there then be a worldwide social scoring system like in China? Would (politically) dissidents or those who deviated from the norm be punished by not having access to the Internet, by not being able to book flights or trains, and thus not being able to move freely? Would it then no longer be possible to discuss in a social discursive process who sets these norms and for what motives? In such a non-democratic society, are there nevertheless the technical possibilities for a new totalitarianism, which perhaps even exceeds that of the 20th century? Can there then still be activities in favour of more democracy if surveillance is all-encompassing? What means of power would then be available to citizens to shape democracy as a lively process through which society is constantly renewed and through which everyone learns – for the benefit of all?

Democracy has the limitation of power by countervailing power, the so-called balance of power, as its precondition. Applied to Big data, this means that the collection, processing and use of data by companies and states alike requires democratic, public control by the whole society. Individual netiquette, so to speak as “rules of conduct” for companies and consumers, is one thing. Laws, data protection rules and their enforcement are the other. Digitalisation is political. If it is to be fruitful and productive in an environment of peace and social progress, this technological change is depending on the rule of law, transparency and a critical civil society, even under changed circumstances. In addition, the transformation processes that go hand in hand with digitalisation once again claim for 'matured' citizens. What is meant by this?

Among many other aspects, it is important to systematically reflect on the “current structural change of the public sphere”. Under these conditions, not only certain contents are relevant if citizens want to navigate in the thicket of information, gain orientation and arrive at a reflected own opinion. It is just as important to understand the “structures of the production of truth” - and to what extent these are the ones that generate certain contents and others not.

This differentiation may also raise awareness of another moment: the problem of “filter interpretations”. It can be observed, for example, that in the context of certain major political events, a particular “wording” quickly gains influence. As a kind of interpretation aid, so to speak, which, however, is often accompanied by an interpretation. This may offer the citizen some orientation. However, quick discursive definitions can also exclude other perspectives and promote the distinction between social milieus instead of initiating an open dialogue, a frank controversy on ideas, by which citizens struggle for truth and democratic values.

“Filter bubbles” and “filter interpretations” therefore lead to the question of the 'truth criterion' of information. In the new complexity of media diversity and in view of the fact that it is impossible to be well informed in all subject areas and thus to compare new information with one's own knowledge, trust plays a major role. A message is more likely to be considered 'true' if the person delivering it appears trustworthy. Therefore, besides factual aspects, the relationship criterion plays a role that should not be underestimated. The boundaries between trust and the simple belief that a message is true can be fluid under these circumstances. There are also other psychological motives: for example, the need to belong. Or the claim to re-find oneself with one's own experiences and perceptions of reality in what is publicly discussed. Or the interest in taking up inspiration, learning new things, understanding what holds the world together - and what does not. Manipulation can be successful above all when these so human needs are not reflected and when it remains unrecognised that these moments influence the emergence of what is considered to be truth.

If big data and 'big democracy' are not to be mutually exclusive, a critical basic digital literacy of citizens is essential. It does not only include competent use of various media and adaptation to changing technical circumstances. The analytical horizon also needs to be extended by taking the political strategy into consideration according to which digitalisation and the handling of big data are put in practise. Which political and economic structures emerge from it as a result? Should they be more liberal, social democratic, 'green', conservative or Marxist? What political direction should be given to the processes of digitalisation and the handling of big data? Why and for what purpose should digitalisation and big data be further developed? What are the limits, what are the dangers and possibilities of using digital technologies? How can the protection of human rights and freedoms be ensured in times of digital change? How can it be prevented that one day Google, Facebook and other corporates will no longer transfer their data to secret services in order to prevent terrorism, but to take action against those who think differently, the so-called dissidents? Digital literacy means also fostering a public and political debate on these questions. In an open, and often analog, discourse, may then emerge what is indispensable for peace and cohesion of a society: trust.

References

Bendel, Oliver, Big Data, https://wirtschaftslexikon.gabler.de/definition/big-data-54101 (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Big data, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_data (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Big Data, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Data (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Bridle, James, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff review – we are the pawns, 02/02/2019, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/feb/02/age-of-surveillance-capitalism-shoshana-zuboff-review (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Data preservation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_preservation (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Elliott, Timo / Schitka, John / Eacrett Michael / Marsan, Carolyn, Data Lakes: Deep Insights, 12/06/2017, https://www.sap.com/germany/trends/big-data.html (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Fachinger, Veronika, Big Data Analytics – Warum Sie diesen Trend nicht verpassen sollten und wie Sie selbst profitieren, 13.11.2018, https://piwikpro.de/blog/was-ist-big-data-und-wie-profitieren-unternehmen-davon (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Holzki, Larissa, Die Vermessung der Mitarbeiter, 21.04.2018 http://www.sueddeutsche.de/karriere/zukunft-der-arbeit-die-vermessung-der-mitarbeiter-1.3953434 (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Luber, Stefan / Litzel, Nico, Was ist Big Data Analytics? 01.09.2016, https://www.bigdata-insider.de/was-ist-big-data-analytics-a-575678 (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Manhart, Klaus, Doppeltes Datenvolumen alle zwei Jahre, 12.07.2011,

https://archive.fo/20131202232836/http://www.cio.de/dynamicit/bestpractice/2281581/index.html (retrieved 30/01/2020)

NetVersity, What is Big Data? (2019), 07.07.2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkOwlXUaGMM

Safar, Milad, Einfach erklärt: Was ist Big Data? Was bedeutet Big Data eigentlich und was sind die Vorteile von Big Data-Technologien?, https://weissenberg-solutions.de/einfach-erklaert-was-ist-big-data, (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Tusch, Robert, New York Times: Einfluss von Cambridge Analytica auf US-Wahlen viel kleiner als gedacht, 07.03.2017,

https://meedia.de/2017/03/07/new-york-times-einfluss-von-cambridge-analytica-auf-us-wahlen-viel-kleiner-als-gedacht (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Vorratsdatenspeicherung, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vorratsdatenspeicherung (retrieved 30/01/2020)

Zuboff, Shoshana, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power, London, Profile Books: 2018

Zuboff, Shoshana, Das Zeitalter des Überwachungskapitalismus, Frankfurt/M., Campus: 2018

Picture:

By Myworkforwiki - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29452425, 2013

Author: Sophia Bickhardt, weltgewandt e.V.

This text is published under the terms of the Creative Commons License: by-nc-nd/3.0/ The name of the author(s) shall be as follows: by-nc-nd/3.0/ Author(s): Sophia Bickhardt weltgewandt e.V., funding source: Erasmus+ Programme for Adult Education of the European Union. The text and materials may be reproduced, distributed and made publicly available for non-commercial purposes. However, they may not be edited, modified or altered in any way.

The European Commission's support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents, which reflect the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Discussion